I often get questions about the economics of book publishing, and about the best ways to support authors. At the same time, I rarely get questions about things I wish more readers knew, like some of the ways that the publishing industry exploits libraries, or the ways social media perpetuates harm to authors. So today, I’m sharing everything I know about the economics of books, and what all of that means for you as a reader (or listener, because audiobooks are books, too!).

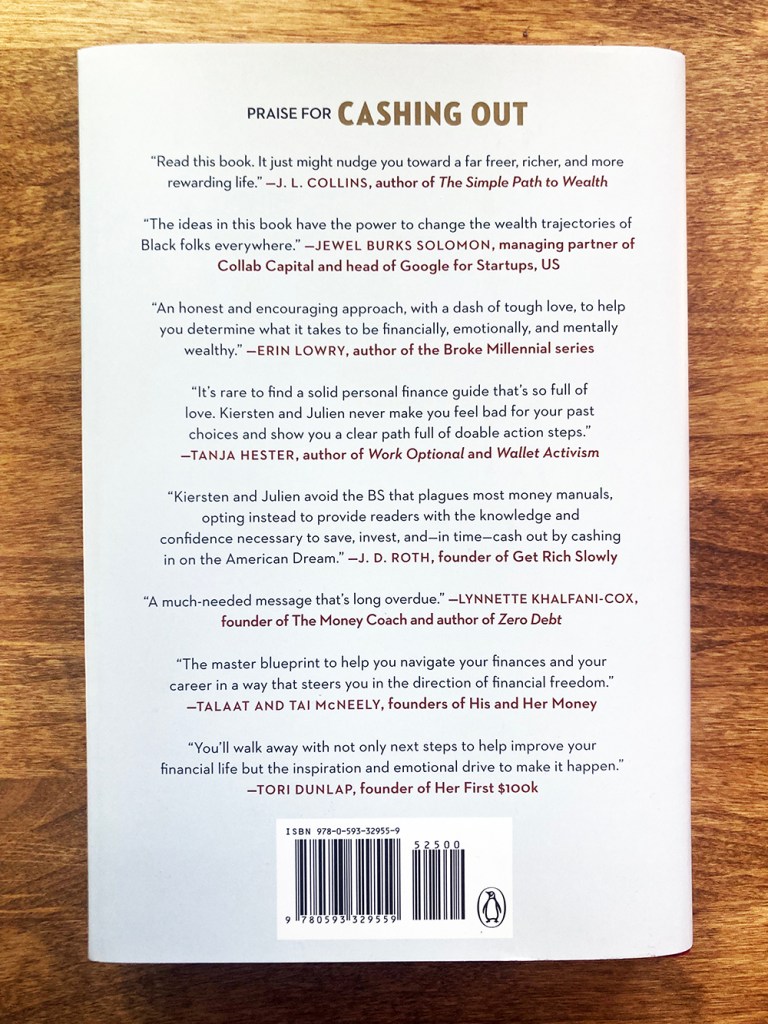

Speaking of books… today marks the release of a book I’ve been so excited about for so long, Cashing Out by Julien & Kiersten Saunders.

I was lucky enough to get an early read, and then honored to get to blurb the book (when you provide a quote in advance of publication).

If you love my books Work Optional or Wallet Activism, you’ll love this book, too. Kiersten and Julien take a super-realistic view of both personal finance and the work world, and offer a plan for exiting a workforce that doesn’t care about most of us, especially Black folks and other people of color. It’s exactly the right mix of hope and realism that we need in a deeply inequitable and unjust world. If you want to order Cashing Out now, you can use this link. And if you want to grab it from the library, or in ebook or audiobook form, keep reading for how to do that in the most ethical way possible. I’m also doing a giveaway for Cashing Out as well as both of my books on Instagram, so go get in on that.

Also new today: a new episode of the Wallet Activism podcast, featuring a conversation with Kiersten and Julien about doing work that’s aligned to your values and your life priorities. You can listen in Apple podcasts, or in your favorite podcast app.

The Economics of Books

On the surface level, the economics of books are straightforward: publishers make money when people buy books. But books aren’t like t-shirts or microwaves where most of them are pretty much the same. Every book is different: different author, different genre, different content, different audience. Though big publishers aren’t clamoring to open their accounting ledgers to the public, it’s generally understood that most books don’t make money for the publishers, and break even at best. (Though it’s not true that a book that doesn’t earn out its advance – more on that in the next section – has necessarily lost the publisher any money.) So it’s the mega bestsellers that pay salaries and keep the lights on and kick profits up to shareholders.

This means that, for as much as people who work in publishing love books and wish they could publish all the good books and proposals that cross their desks, publishing is absolutely driven by what the people in charge think has the best chance of being a big seller. And that makes sense! Their goal is to stay in business, which means staying profitable, and to do that, you have to be good at picking books to publish that will sell a lot of copies, and minimize the number of low-selling books you publish.

The problem is that chasing books you expect to be profitable means mostly publishing books that look a lot like books that have come before it. Which is why publishing has such a well-documented diversity problem. The vast majority of books that have gone on to be bestsellers were written by white men, and thus many more books by white men continue to be published. Despite a big push to diversify publishing, New York Times data show that roughly 90% of books published are still by white authors, and men are still much more likely to be published despite women accounting for the majority of book sales in many segments, and two-thirds of overall books sold. (I will spare you stories of how many times men have told me that it’s nice someone finally wrote “a FIRE book for women,” talking about Work Optional, assuming it was only for women just because I am a woman. Publishers experience this bias, too, because they know the stats are bleak on men reading books written by women.) The need to chase profits also limits the types of books publishers are willing to publish. For example, when we were shopping my proposal for what would become Wallet Activism, many publishers told us that books on social and environmental issues didn’t sell well, so they weren’t willing to take the risk, even if they loved the idea and hoped they’d get to read it.

All of this means that, like so many of our financial decisions, the choice to buy a book is actually a choice about the kind of world we want to live in. (Translation: book buying is political.) Do we want to live in a world that keeps publishing the same kinds of people writing about the same kinds of topics, or do we want to live in a world with much more diversity of authors and experiences represented in the books we can buy? How you answer that question should absolutely guide you in your decision-making. But first, here are some more facts about books and money.

How authors get paid – An author gets paid two ways: via royalties on copies sold, and via an advance against royalties, usually just called an advance, which is any money a publisher offers upfront to lure the author in. The average advance is somewhere in the $5,000-20,000 range, and the vast majority of authors never earn out their advance, meaning that’s all the money they’ll ever receive for all the work of researching, writing and promoting a book, and that’s not counting the 15% or more that the author’s agent will take off the top. (The agent cut is totally worth it if you have a good agent!) As Danny Iny wrote in Inc., “A typical book author barely makes more than minimum wage. You receive an advance and 10% royalties on net profit from each book. If your book retails at $25 per copy, you would need to sell at least 4,000 copies to break even on a $5,000 advance.” Note that he says NET profits. If a book retails for $20, the author isn’t getting 10% of $20, they’re getting 10% of whatever the bookseller paid the publisher, which is usually half the cover price at most, and then the publisher often subtracts printing and shipping expenses at a minimum. So if an author has earned out their advance, they might make $.50 to $1 on the copy of the book you buy, but if they haven’t earned out, they might make nothing additional. You can read lots of accounts like this one of authors earning very little despite strong sales. It’s also worth noting that every book contract is different, so authors might make a bit more or a bit less on different formats of the book, they might sell rights to different formats separately, or they might forgo an advance altogether to get a higher royalty rate. If you don’t care what format you read a book in and just want to support the author, ask them what format they would like you to purchase, and know that it might be different for different books they’ve written. (Best for me: buying the Work Optional audiobook and the Wallet Activism paperback.)

(Remember, the royalty rates here are on net profits, not sticker price. Source)

Self-publishing vs. traditional publishing – I often hear people talk about traditional publishing as an evil industry that exploits authors, because it’s true that an author might make anywhere from nothing up to a dollar when you buy a traditionally published book, while a self-published author makes substantially more from each sale. But that leaves a lot of important information out! The biggest problem with self-publishing is that the author has to pay for everything out of pocket before making a single sale. Need to hire a developmental editor to make the overall book stronger? You pay for it. Need to hire a copy editor to check for mistakes? You pay for it. Likewise for book layout, cover design, indexing, and certainly any marketing and promotion work done. Authors can easily run up many thousands of dollars in expenses without earning a penny, and there’s no guarantee the book will sell and you’ll make that money back. (Or they skip some of these steps and the book is worse for it.) With traditional publishing, publishers pay all or most of these expenses and take on essentially all of the risk, depending on the deal, so you trade a lower backend cut for no upfront expenses (and, usually, money upfront as an advance). Self-publishing can still work out well for some authors, especially those who sell a bunch of copies, but it’s important to be clear-eyed about the pros and cons of both, especially because no one can see the future. It’s also worth knowing as a reader that self-publishing can certainly mean that the book went through substantially less editing and could be totally unvetted in terms of validity.

Awards – It might surprise a lot of people to know that awards and honors don’t typically boost book sales. Wallet Activism has now won three awards and was finalist for a fourth, and none of those awards changed the trajectory. Awards are still nice to get, of course, but they don’t impact sales.

Press coverage – Similarly, getting great press coverage does much less than you might think to boost book sales! You can have the most glowing review in the biggest news outlet imaginable, and it won’t change the book’s trajectory. What does sell books? Social media posts! Word of mouth! Endorsements from people whose opinion your readers value. (And a publisher paying bookstores for prime placement in the stores, but that’s a different subject.) So if you love a book, talk about it on social, and do it more than once. That’s a great thing you can do to support authors.

How to Buy Physical Books, eBooks and Audiobooks Without Amazon

If you decide that shopping with Amazon doesn’t align to your values (a view I’m not trying to push on you, by the way, though it’s a choice I support), that doesn’t mean you’re limited in your book-buying choices, nor does it mean that you can only read physical books. A common misconception I hear a lot is, “I would love to stop buying from Amazon, but I have a Kindle!” The good news is that having a Kindle does not limit your options.

Physical books – You have by far the most options when buying physical books. You can buy them in-person at your local, independent (non-chain) book store, you can buy them at a chain like Barnes & Noble, or you can buy them online. (Note that authors don’t benefit if you buy books secondhand or from the discount rack.) Bookshop.org has quickly become a favorite among online book buyers because they discount the book price and they kick a portion of sales back to local indie bookstores. But there are tons of great options:

- Bookshop.org – Be sure to choose your local store in the upper right corner (the link is to my storefront, with lots of books I recommend).

- Indiebound – Connects you to your local store so you can shop online but still buy local, or just check to see what your local store has in stock so you can go buy a book you want in person.

- List by state of bookstores owned by people from marginalized groups – Includes Black-owned, Latine-owned, Indigenous-owned, LGBTQ+-owned, disabled-owned, etc.

eBooks – You might be surprised to learn that you CAN likely buy ebooks from your local bookstore! Go to their website, search for the book you want, and the site might show you multiple formats available, or you might be able to scroll down to the bottom of the page to find the ebook option. It’s important to note that ebooks come in multiple formats, and not all formats are initially compatible with all brands of ebook readers, but it’s easy to convert ebook files from one type to another. You might want to test out converting one book (and perhaps use a library book to do it, so you’re not out any money) before you go nuts buying books in a format not initially compatible with your device, but then you’ll see you have so many options. You can buy ebooks at all of the stores listed above, and you might also try Smashwords, which lets self-published authors get into libraries.

Audiobooks – Just like ebooks, you can often buy audiobooks directly from your local indie bookstore, or from Bookshop.org, though almost all of those stores use the Libro.fm platform, which you can also buy from directly. And that’s great because Libro.fm kicks money back to local indies just like Bookshop.org does. They also give you multiple options to buy, so you can either pay a monthly membership fee and get credits to buy books (basically identical to the Audible membership), or you can buy an audiobook as a one-off purchase.

The Economics of Libraries

I love the library. Truly one of the biggest bummers of the pandemic for me has not being able to write at the library. I wrote almost all of Work Optional at the library, and loved having the change of scenery as well as having all the research materials I could ever need right there. But, despite my everlasting affection for every library ever built, I’ve changed how I use the library after learning some pretty startling facts about how they are forced to operate. Perhaps you’ll have a change of heart, too.

The most basic fact about the economics of libraries is this: libraries pay for everything they lend out. If you see a physical book sitting on a shelf, they bought that book. If you see an ebook or audiobook listed on OverDrive or Libby, the library paid for those digital copies. Libraries are generally operated at the county level and are funded by tax dollars, and librarians work hard to meet the demand of their library visitors while staying within their budget. That part is straightforward.

Here’s where it gets icky. While libraries generally pay the retail price for physical book copies (if the book says it’s $17.95, that’s what the library pays, and then they can keep lending out that physical copy until it wears out), when it comes to ebooks and audiobooks, it’s a very different story.

Because publishers are so worried that library ebook lending is driving down sales, they’ve forced pricing on libraries that is, frankly, obscene. An individual can buy virtually any ebook for $10-15, or might get lucky and find it priced at $3 that day, and then they get to keep that ebook forever, and can revisit it in 30 years if they want. Libraries, however, pay much more, and then they don’t even get a perpetual license on the copy they’ve just bought, they only have it for a short period of time or a certain number of lending periods. While the terms vary by publisher (there’s a chart at the bottom of this post breaking things down), for most books published or distributed by the Big 5 publishers (which includes most popular books), libraries are paying $40-60 on average per licensed copy (often more for the audiobook), and then that license expires after two years at most, when they either have to pay the price again or lose the ability to lend that book out digitally. Some publishers are also barring libraries from buying more than one copy of an ebook during the first eight weeks after publication, to avoid cannibalizing sales. (Oh, and Amazon won’t let libraries buy and lend out ebooks and audiobooks published on its platform at all, which is, somehow, worse.) If you want to read more about this, there’s a helpful New Yorker story on it, and an even better introduction with lots of links for further reading from the Denver Public Library.

Library ebooks and audiobooks are wonderful, and borrowing them is convenient as hell. You hop on an app, click borrow and away you go. But I think some of the enthusiasm folks feel for easy digital lending would be blunted if folks knew how much this system is costing libraries.

Beware of BookTok Advice

While I love any space where people talk about books, some BookTokers have apparently been saying in their videos that you can buy the Kindle version of a book on Amazon, read it quickly, and then return it for a full refund within seven days, so you’re getting to read it for free. Don’t do this!

As author Lisa Kessler tweeted:

Amazon appears to charge some authors when readers return their books, apparently under the assumption that the book must be junk if someone is returning it. As I’m published through large publishing companies, I don’t have access to my Kindle book agreement language and can’t confirm this, but lots of authors are speaking up to report that they owe Amazon money for returns, too. People are reportedly reading through authors’ whole series (which you wouldn’t do if you didn’t enjoy the books) and then returning them so that the authors owe money out of pocket. Needless to say, authors having to pay readers to read their books, rather than the other way around, is not a sustainable business model.

Related: I helped Vice debunk bad money advice on TikTok

So what can you do about all this? Several things! 1. Sign the petition to get Amazon to change their policy, so they stop punishing authors. 2. If you like to buy ebooks, buy them elsewhere (see above for lots of options!). 3. If you like to read for free, get your ebooks from the library. Despite all the problems with the ebook pricing for libraries, it’s still a better system than making the author pay so you can read their work.

How I Buy and Borrow Books Now

As I always stress, there are rarely “right answers” when it comes to ethical decisions, so it’s up to you to figure out what feels right for your circumstances. But in case you’re curious, here’s the approach that I’ve settled on for my reading choices. My general philosophy is, “I want to live in a world with more books, by a more diverse range of authors, and on a broader range of subjects,” so that means it’s on me to create demand for that world by putting my money behind that desire, a cornerstone of my Wallet Activism philosophy.

For books by friends and others I want to support, I always buy the book. Lots of people now send me their books for free, but I’ll still buy a copy and give it away, because supporting authors whose work I value is important to me. The same goes for books on topics that I want to see more of that aren’t otherwise represented in publishing. I want publishers to see value in publishing a broader spectrum of voices and books, and I vote with my dollars to show them. If it’s a book I want to keep for a long time, I’ll buy the hard copy, but otherwise I’ll buy the ebook or audiobook, especially if the author narrated the audiobook themself, to avoid something needing to be produced and shipped. And for books I really want to support, I request the library buy ebook and audiobook copies when the book is released, because I’d rather those books get bought than others that don’t bring anything new to the table.

For authors who are clearly doing just fine without my help (think New York Times bestsellers), I generally get their work from the library. In the past I’d always try to get the ebook or audiobook, but based on the exploitative pricing libraries are subject to, I generally look to see what the waitlist situation is for the book. If it’s been out a while and there’s an ebook or audiobook copy available to borrow right away, I borrow it. The library has already paid for it, and the clock is ticking on that license, so there’s no reason to hold off on borrowing it that way. But if there’s a long waitlist, I generally decline to add myself to it, and either try to get the physical book from the library, or I just buy the ebook if I want it badly. If the library doesn’t own a digital copy, I no longer request that they buy a copy unless it’s an important book that needs the support, given the pricing.

Something else I do in response to learning about the library digital pricing: I try to stay on top of what ebooks and audiobooks I have checked out and quickly return books I know I’m not going to get to during the lending period. I also try to read and listen to the ebooks and audiobooks I check out quickly, and return them well before they are due rather than just letting my borrowing period expire. My hope is that someone else can read them in that time and make the high price the library paid a little more worthwhile.

Questions?

Do you have questions about book economics that I haven’t covered here? Tweet at me or respond to my Instagram post on this topic, and I’ll answer you there. Happy reading!

Don't miss a thing! Sign up for the eNewsletter.

Subscribe to get extra content 3 or 4 times a year, with tons of behind-the-scenes info that never appears on the blog.

Categories: book